Back in the day there was an inventory-management convention that proscribed days’ supply should not get above 65-70 days. It wasted cash.

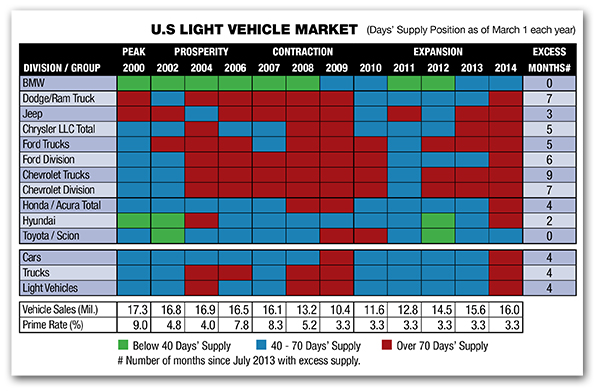

If we look back to the last market peak, that rule seemed to be a normal inventory practice for light-vehicle producers. For the most part, it was the norm during the sales expansion period that lasted through 2006.

It made sense. Interest rates were high and the cost of carrying more than the norm was fairly prohibitive. One thing is certain: Inventory is not cash. Excess inventory is waste, an activity that absorbs resources but creates no value. The Japanese call it muda.

As the vehicle market declined through 2009, this good practice of inventory control lost favor, piling on weight to the financial pressure that existed at the time. No surprise here.

Overall inventory management improved dramatically during the expansion years. From 2010 through 2013 total inventory remained below 70 days’ supply, even in the presence of low interest rates.

Both dealers and manufacturers improved their cash positions as a result. They also didn’t have significant pressure to provide incentives to clear the lots.

Recently, the industry has lost its way on inventory control. For the past four months, automakers have left excess inventory on dealers’ lots. Not a good sign. Cash could be used for better purposes.

Looking at specific brands, one defines the gold standard of inventory management: BMW. Admittedly, BMW keeps its inventory tight, sometimes short, but rarely is it in excess. Toyota and Hyundai also have demonstrated lean thinking when it comes to inventory management.

However, practices have been less than stellar at the Detroit Three. Now, here come the excuses for bad inventory management (more than 70 days’ supply or less than 40): “You never want to be short” or “The model lineup is very complex,” or “We are changing our models at a faster rate.”

Balderdash. The Detroit Three have practiced sloppy inventory management for quite some time, with a few exceptions through good times and bad. During the past nine months it has gotten worse, a testament it is not about selling problems just with the winter months.

Is this the new normal? For the Detroit Three the answer is no, it seems to be an operating principle. The only thing helping them through the current environment is low interest rates. If interest rates start to creep up, we could see dealers balking at taking on more metal.

It is highly unlikely the market will expand for six years in a row. Manufacturers that are in excess today need to clear the swamp (in other words, balance production and demand) before the market softens further or interest rates rise.

If not, the tradeoff between profits or production will be much harsher in the middle of a downturn.

Let’s hope improved balance sheets at the Detroit Three enable a shift away from what appears to be, unfortunately, normal.

Conventional wisdom among economists is that about half of the downswing of economic activity in business cycles is due to consumers and producers working off inventories built up at the top of the cycle, a pattern noted by James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones in their book “Lean Thinking.”

If inventory gets under control, profits will go back to dealers and the factory; otherwise a good proportion simply will end up with the customer in the form of increased incentives.

Warren P. Browne is president of WP Browne Consulting and has extensive experience in the global automobile industry. During the past 20 years, he has held senior executive positions at General Motors, including in Brazil, Poland and Russia. He currently serves as an adjunct professor of economics at Lawrence Technological University.