It could get ugly.

But opinions differ on how badly Europe’s new-car market may deteriorate, what actions governments should or shouldn’t take as a result and how it all will impact auto-industry jobs and OE strategies.

Like chapter after chapter in a page-turning crime novel, 2012 is winding down with a multitude of cliffhangers, and it is anyone’s guess which turns the plot will take and what characters may find themselves in a battle for their lives in the new year.

Among issues that will linger into 2013 are costly industry overcapacity – estimated by some analysts as high as 5 million vehicles annually – and a still-shaky eurozone that is curbing consumer confidence and tanking new-car demand.

A price war is wringing profitability out of several car makers’ ledgers and adding to the drama, as is an outbreak of industry infighting and name-calling.

A price war is wringing profitability out of several car makers’ ledgers and adding to the drama, as is an outbreak of industry infighting and name-calling.

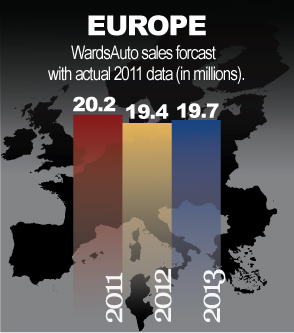

As 2012 draws to a close, WardsAuto projects industry sales to decline 4.2%. But several major markets are in freefall, including Italy, expected to post a 21.4% drop for the year; France, off 11.8%; and Spain, down 10.5% from already anemic 2011 levels. Even Germany, which had bucked the trend, is seen slipping 1.2%.

Soft sales are tamping down production in the region, expected to finish the year 4.3% below 2011 levels, at 19.45 million vehicles in the 25 countries forecaster AutomotiveCompass tracks. Output in Germany will erode by 6.9% this year, while Italy will be down 7.8% and France off 5.9%.

While everyone agrees there’s too much vehicle-production capacity in Europe, there is no consensus on what to do about it, and there’s some question whether industry, government and labor leaders have the fortitude to address the issue at all.

Garel Rhys, president of the Center for Automotive Research at Cardiff University, pegs real overcapacity in Europe at closer to 2 million-2.5 million units, and says there finally may be the will in individual markets to withstand the needed handful of factory shutdowns.

“The political climate has changed,” he says. “And most countries don’t have the billions of euros that would be needed to protect their industries. It’s going to be an interesting period.”

Fiat CEO Sergio Marchionne has used his position as this year’s head of the ACEA, the European manufacturers group, to stump for a European Union-brokered capacity-reduction roadmap for the industry overall, coming under fire from Volkswagen, which trumpets its survival-of-the-fittest philosophy that would solve the problem through natural attrition.

Rhys sides with VW, saying Marchionne’s proposal “is not going to fly. It’s a very headstrong argument. Everyone sees through it.”

France’s PSA Peugeot Citroen and Germany’s Adam Opel already have announced plans to decommission one assembly plant each. But Opel continues to wrangle with labor unions over how to wind down its Bochum, Germany, facility in 2016, and PSA has had to face the headwinds of strong opposition from both labor and government officials over a proposal to shutter its Aulnay operation near Paris in 2014.

France’s PSA Peugeot Citroen and Germany’s Adam Opel already have announced plans to decommission one assembly plant each. But Opel continues to wrangle with labor unions over how to wind down its Bochum, Germany, facility in 2016, and PSA has had to face the headwinds of strong opposition from both labor and government officials over a proposal to shutter its Aulnay operation near Paris in 2014.

Fiat, also stuck with declining sales in Europe and more assembly firepower than needed, is staring into a similar abyss. The auto maker this month saw its credit rating downgraded by investment firm Moody’s as a result of its underutilized factories, running at only half speed in Italy.

But political pressure there has Marchionne reluctant to propose any permanent shutdowns. Instead, he is hinting at a more palatable plan of shorter workweeks and boosted exports to soak up some of Fiat’s unused capacity, while continuing to lobby for a broader solution that would help dial back some of the heat on the auto maker.

In a confab with reporters at the Paris auto show in late September, Marchionne shies away from offering too specific a plan, but calls on the EU to step in to prevent state governments from dangling enticements that would influence auto makers to keep plants open in one country and close them in another.

“Europe is struggling with how to (address overcapacity), because of national boundaries,” says Marchionne, who believes the prospect for widespread plant shutdowns has increased in recent months as industry sales have continued to spiral.

No new free-trade agreements should be signed until the EU is on better economic footing, he says, alluding to a controversial deal with Japan expected to kick in by year’s end that some fear could open the floodgates to imports.

“We need to be able to allow car makers to bridge over to the next phase. What I want from the government is a level playing field for anybody to compete.”

Later that day, Spain announces a new scrappage program meant to pump up vehicle sales and sustain local manufacturing, proving Marchionne’s point that even in the current tough economic climate individual countries may have a difficult time standing by idly while their industrial bases erode.

Last week, the French government signaled it may be willing to guarantee €4 billion ($5.2 billion) in loans to PSA, further playing to the Fiat CEO’s fears.

“(Governments) know that car makers’ attempts to safeguard the business is the only way forward,” Renault and Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn assures The Wall Street Journal.

Renault has not alluded to closing any plants, however. Instead, Ghosn’s strategy to survive the downturn appears to be greater synergy with Nissan – additional shared savings of €4 billion ($5.2 billion) is targeted in 2016 – and an increasing involvement with Daimler, sharing expensive powertrain and platform technology, as well as some capacity.

“We are not sitting there with our calculators,” says Daimler CEO Dieter Zetsche, “but the benefits are a billion number, not a million number. So many good ideas are cropping up.”

Susan Docherty, head of Chevrolet and Cadillac sales in Europe, says margins are being squeezed to dangerous levels as auto makers do whatever is needed to move the metal and keep underutilized assembly plants humming.

“It kind of feels like what I saw (in the U.S.) in ’08 and ’09 in terms of the fundamentals,” she says. “We’ve got a European debt crisis here. We’ve got lots of pressure on the industry. The OEMs are putting incredible amounts of incentives on their products because their inventories are too high.

“I am seeing incentives that are anywhere from 20% to 30% of gross sales, which is unbelievable.” Docherty says. “Very scary numbers. Nobody can make money with incentives like that.”

Ford’s Roelant de Waard, vice president-marketing, sales and service in Europe, appears to be taking it all in stride, telling WardsAuto, “(Incentives) clearly have gone up by multiple percentage points. But that’s logical. Everyone’s looking for the marginal sale.”

Like the others, Ford is facing huge financial hurdles in Europe, where it expects full-year losses to top $1 billion in 2012 and is looking for ways to trim production costs.

Ford’s Genk, Belgium, facility is a rumored candidate for the chopping block. But in the meantime, a lot of less “spectacular” moves to change shift patterns and shorten work weeks have been made, de Waard says, though he cautions against knee-jerk reactions to addressing overcapacity.

Ford’s Genk, Belgium, facility is a rumored candidate for the chopping block. But in the meantime, a lot of less “spectacular” moves to change shift patterns and shorten work weeks have been made, de Waard says, though he cautions against knee-jerk reactions to addressing overcapacity.

“You can restructure, but you are taking out a lot of assets forever,” he tells WardsAuto in a Paris interview. “You could argue whether that present (market) demand level is the true demand. As much as it was artificially high (five years ago), this may be artificially low.”

Rhys agrees. “If you cut, cut, cut, you destroy the economies of scale.”

In the end, the problem may not be about the amount of capacity as much as where it is located, de Waard says. “Because of import-duty legislation, the capacity can’t find its way around the market very easily.”

Ford looks downright healthy next to Opel, which has been mired in red ink for most of the past decade but is vowing to stay in the game.

New reports surfaced in early October that General Motors is considering further ties with PSA that could include folding Opel into a joint venture with the French auto maker. GM reportedly would chip in $10 billion in cash toward the JV.

In February, the two auto makers agreed to combine some purchasing functions and potentially collaborate on future B- and D-segment vehicle programs, a plan that was expected to save a combined $2 billion annually beginning in 2017.

But the initial phase, which saw GM pay €320 million ($415 million) for a 7% share in PSA, appears to be off to a rough start. Because PSA’s financial fortunes and stock prices continue to decline, GM may be forced to write-down its investment. And despite months of exploration, no firm plan on product sharing has been revealed.

French officials also have been less than ecstatic about the GM tie-up, believing the move will destroy PSA’s independence and take a bite out of the country’s industrial complex.

Work to streamline Opel continues independently of PSA, with plans to take down capacity and slash some 1,000 administrative positions at its Russelsheim headquarters, while still maintaining a product program meant to emphasize the brand’s stakes in German engineering and advanced technology.

Mike Abelson, vice president-engineering, says the job cuts won’t affect his group, with Opel planning 23 new or revised vehicles and 13 new powertrains by 2016.

“We know the core of any turnaround in the automotive business is the products,” he says. “If you don’t have the products, you can’t execute, you can’t make a significant improvement in the business.”

Ford, which has seen its market share erode in the past year, also is on the verge of a new-product drive, now launching its EcoSport small cross/utility vehicle and rolling out a new model in the Transit commercial-vehicle line in October. Those will be followed over the next few months by a new Kuga CUV and revamped Fiesta. A new Mondeo will bow later next year, as will additional models in Ford’s CV line.

“All those products will arrive in the market when we start seeing it come back. So we think the timing is perfect,” de Waard says.

Fiat isn’t so sure.

“The European market, having lost 3 million cars in the last five years has got drastic consequences,” says Marchionne, who is slowing new-product investment in the face of the collapsing sales, much to the chagrin of labor leaders in Italy.

“When we hear requests from some of the unions that we need to invest anyway, when you know that you’ll never be able to recover capital, you’ll never be able to earn anything on the investment, I wonder if we all share the same view.”

Forecasts are being revised almost daily following August and September sales declines that missed few manufacturers. WardsAuto predicts demand in the region will inch up 2.0% in 2013, as gains in Central and Eastern European countries offset declines in more traditional markets. Germany is likely to slip slightly next year, while Spain continues to slump and France sales remain flat.

Forecasts are being revised almost daily following August and September sales declines that missed few manufacturers. WardsAuto predicts demand in the region will inch up 2.0% in 2013, as gains in Central and Eastern European countries offset declines in more traditional markets. Germany is likely to slip slightly next year, while Spain continues to slump and France sales remain flat.

“We’re not seeing any quick fixes to this. It’s going to be a very interesting year,” Docherty notes, adding most forecasts she has seen are “overly optimistic.”

“You have very high unemployment of 10.3% in Western and Central Europe, decreasing confidence and, (where) in the past some of the countries have been able to stimulate the industry through scrappage programs, the countries are in such a state they don’t have the ability to pull those levers.”

De Waard agrees cash-strapped governments may be reluctant to follow Spain’s lead with a sales-inducing scrappage campaign, but adds optimistically: “You can’t save your way to success. You have to maintain a certain level of economic activity. You want to protect some of your infrastructure, because we are still in business cycles. It will get better one day.”

Bright spots include Russia, which is forecast to gain 14.2% in new-vehicle volume this year and another 8% in 2013.

“(Russia) is expected to be the largest market in Europe – within five years is probably conservative,” de Waard says. “It could be there already next year.”

Luxury-car makers such as Audi, BMW and Mercedes continue to report strong, if not record, sales, while A- and B-class vehicles are emerging as a hot segment for volume makers as state governments creep up value-added tax rates to raise revenues and European customers downsize to save money.

But the big question remains as to whether plant closings, high unemployment and anemic consumer confidence will prevent the European market overall from finding its bottom in 2013 or signs of recovery will emerge, pointing the way toward better days in 2014.

Rhys is convinced Western Europe will return to peak sales levels of 17 million vehicles annually, but believes significant recovery won’t come until 2017.

“The automotive industry is cyclical; it always has been,” sums up Opel’s Abelson. “It will turn around sooner or later.”

But by then, the European auto industry landscape may have a somewhat different look.