Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

Sarah Lee-Ellena strides confidently from the chapel to the foyer of Lee-Ellena funeral home in Macomb Township, MI, extending a hand in a greeting that is part former car dealer, part suburban undertaker.

“Welcome,” she says, standing under a skylight that transmits brilliant colors around the Frank Lloyd Wright-inspired gathering room.

Lee-Ellena oversees a $4 million, 16,640-sq.-ft. (1,545-sq.-m) building with three chapels, hospitality suites, a grief library, children’s playroom and an outdoor deck overlooking a 10-acre (4-ha) wetlands.

At 62, she devotes her days to providing sanctuary for bereavement and hospitality for mourners, a different world from the hustle and bustle of her former job running her father’s defunct Oldsmobile dealership.

In its glory years, Bill Lee Oldsmobile was one of the largest dealerships in the northeast Detroit suburbs, with 45 employees and vehicle sales of nearly 1,000 annually.

The store folded in 2004 when General Motors killed off the 107-year-old Olds brand and gave buyout packages to its dealers.

“I was far too young to retire and buying another dealership was too expensive,” Lee-Ellena says, looking back on her dramatic career change.

She enrolled in Wayne State University’s mortuary science department and finished a 4-year program in less than two years.

The former dealer believed that as a funeral director she could break even in three years with a fresh approach to what Thomas Lynch, author, poet and undertaker, calls “the dismal trade.”

As a funeral director, Lee-Ellena says she uses skills honed as a car dealer, including attention to customer service and participation in community activities.

“Most graduates become licensed professional funeral directors and do so with the passion to assist a society that in most cases has difficulty facing death or the loss of a loved one,” says Peter D. Frade, chairman of Wayne State’s mortuary school.

“Sarah was an extremely conscientious student who knew exactly what she wanted from the program.”

Lee-Ellena wasn’t alone as a dealer principal making a momentous career transition.

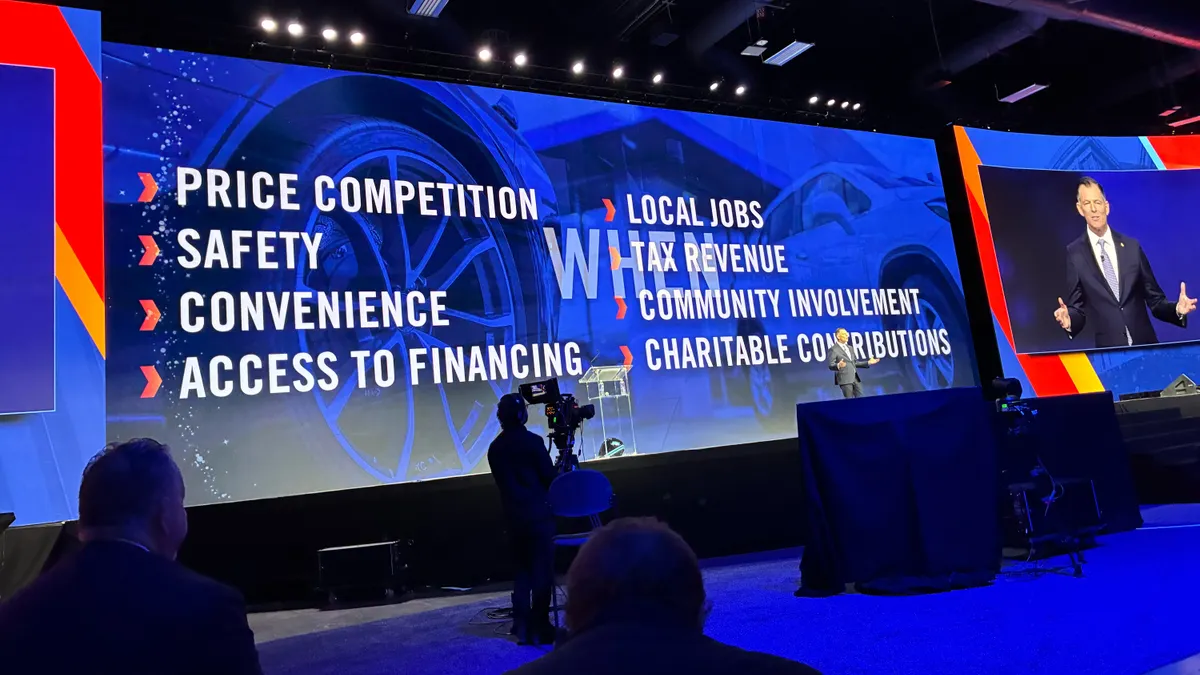

Compared with about 17,500 now, the U.S. once had 60,000 franchised dealerships, says Ken Nash, vice president-strategic and corporate alliances for Northwood University in Midland, MI, a school with a leading auto-retailing program.

“Car dealers are some of the greatest entrepreneurs in the world,” Nash says. “They are excellent at real estate, customer service, community relations, franchise development and financial management.”

Northwood doesn’t maintain a specific alumni organization of former car dealers or what they do now. Nor does GM. But the question of where former dealers have ended up piqued Nash’s curiosity. He plans to conduct a study on the economics of the buyouts.

About 1,490 Oldsmobile dealers were reimbursed for the loss of their franchises under a formula payment of $1,575 to $3,000 for each new car sold in the dealership’s best sales year, between 1998 and 2000.

GM dealers who lost franchises after the auto maker declared bankruptcy in 2009 were less fortunate.

The GM dealer population shrank from 7,700 active dealerships in 2002 to 4,400 today, a GM spokesman says.

What do some dealers do when their operation closes because of a corporate buyout or consolidation? A sample of 11,000 executives served by national outplacement experts Right Management found 5% to 8% became self-employed and up to 62% landed positions with salaries equal to or higher than before.

Their future depended on a strategic search and a willingness to relocate, says Right Management’s John Patricolo, a regional executive vice president.

Relocation wasn’t an option for Lee-Ellena, with frail parents, a husband and a stepson. She chose the entrepreneurial path, using the buyout to help capitalize the funeral home she opened in spring 2008. She turned to a top-rated architect to design the building.

But it wasn’t easy when the recession gripped Detroit and both Chrysler and GM filed for bankruptcy. People in metro Detroit cut spending on funerals along with everything else.

Lee-Ellena talks about her life as a dealer and as a funeral director:

WardsAuto: What qualities did you bring to the funeral business that you learned in selling cars?

Lee-Ellena: I believe the time is ripe for a very different kind of funeral home, one that is friendly and inviting. We didn’t want heavy curtains and Queen Anne chairs. Instead, we wanted the Pottery Barn look.

We chose high ceilings that allowed beams of light inside. We designed a gathering place that looks more like a lodge, someplace comfortable for both the family and guests. Remember, we’re helping families cope during the worst part of their lives.

WardsAuto: What is the most critical difference between selling cars and conducting funerals?

Lee-Ellena: Forecasting. You can’t predict how many people will need your services in the course of a month or a year. You could generally predict how many cars you’d sell because people often bought vehicles on a regular cycle. You could build up excitement with each model year and showcase the inventory on your lot where thousands of cars passed daily.

WardsAuto: How do you build your current business?

Lee-Ellena: We try to change people’s fear of death and denial. We speak with financial planners, chambers of commerce and community groups about estate planning. It is a product with needs and benefits.

Today’s funeral insurance is a low risk for clients. People make checks to a third-party held by reputable firms. That assures clients that the merchandise and level of service they selected will be available when they or a loved one passes on.

WardsAuto: What advantages do you have in the funeral trade?

Lee-Ellena: We don’t need a large inventory of caskets. We carry five or six samples on consignment and don’t pay for them until purchased. With just-in-time ordering, people can select a style from a catalog and have it delivered to the funeral home the next day.

Clients have the option of renting a casket for $1,300 and go the cremation route or purchase it outright for $3,000 or more. We have a permanent staff of four people and bring in greeters and other personnel as the need arises.

WardsAuto: What is the downside?

Lee-Ellena: When you run a dealership, you can go home at the end of the day. Death does not take a holiday, nor does it respect weekends. The only way to avoid burnout is to take time off and get someone else in the company to fill in for you.

WardsAuto: What is the best skill you honed in the dealership?

Lee-Ellena: How to talk to people. How to listen with empathy. It is a calling.

WardsAuto: What was one of your most difficult assignments?

Lee-Ellena: I coordinated the funeral arrangements for my father, Bill Lee. He was 87. It was quite a show. We parked an Oldsmobile Ninety Eight in front of the building and invited the Motor City Rockets Club to lead the funeral procession.

After it was over, I felt the waves of grief that my clients often express. The experience helped me hold more compassion for my clients and ask the right questions to help celebrate their loved one’s life.

WardsAuto: Are you sorry you didn’t stay in the car business?

Lee-Ellena: The recession has been brutal on the car industry. I could have invested everything I received from Oldsmobile on another franchise and lost everything on the next round of cutbacks that favored the larger dealership organizations.

WardsAuto: Are you profitable?

Lee-Ellena: We are turning the corner. I feel like I’m doing an important public service and that counts for much.