Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

Dealers in 2014 are bracing for round two of a fight with a federal agency over how they’re compensated for arranging auto loans.

At issue is dealer reserve, the practice of dealers adding to the interest rate of a loan as compensation for acting as middlemen between car buyers and lenders.

The average add-on is less than 1%, and dealers say it is wrong to assume a car buyer would get a lesser loan rate with dealer reserve out of the picture because lenders offer wholesale, not retail, rates to dealers.

Critics say the reserve system, the centerpiece of dealer-assisted indirect financing, is a rip-off. Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) is one of its most vocal detractors, claiming consumers are “tricked out of billions of dollars every year on car loans.”

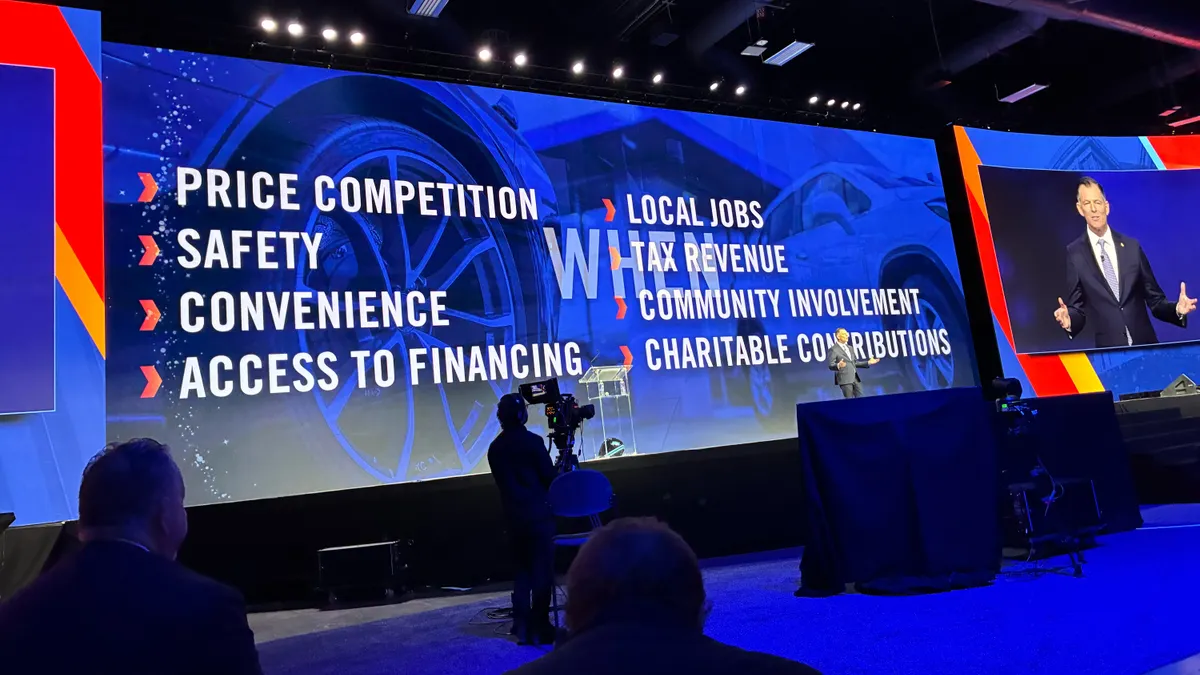

But dealers say the indirect-financing system fosters competition and benefits consumer. Dealers aren’t reserved about defending the lending model.

It became a hot topic in 2013. The debate is expected to get more intense as dealer trader groups try to fend off a government agency’s opposition.

The National Automobile Dealers Assn. warns consumers will be ill-served by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s efforts to prod lenders to end the interest-rate compensations.

NADA contends the CFPB is seeking to change dealer-assisted financing in a way that will increase the cost of credit and make it less available to automotive consumers.

Instead of dealer reserve, the CFPB prefers a flat rate or something like it. The bureau indicates a flat fee might eliminate dealers potentially charging higher loan rates to so-called protected classes of borrowers, such as minorities, creating what the government calls a form of discrimination referred to a disparate impact.

In 2013, the CFPB warned some lenders about the possibility of such pattern of discrimination.

NADA President Peter Welch says the CFPB is withholding information relative to the methodology it is using to determine whether statistical discrimination exists in auto lending. Until it is released, there is no way to determine if the government analysis is reliable, he says.

For example, it’s not publicly known if the analysis accounts for variables such as credit score, the amount financed, term of the loan and special finance incentives.

“There is no place for discrimination in the car business or any other business,” says Welch. But the CFPB’s solution hurts consumers more than it helps, he adds.

“The financing model has worked for a century but now it is being threatened,” says NADA Chairman David Westcott. Indirect lending accounts for the majority of car loans.

Technically, the CFPB has no business overseeing dealer business. After NADA lobbying, dealers won exemption from increased government regulation called for in the Dodd-Frank Financial Reform Act passed after the financial meltdown of 2008.

The consumer protection bureau directly oversees lending institutions that provide car loans with dealers acting as middlemen. By exerting pressure on lenders, the bureau has threated the dealer-reserve system.

On another battlefront, franchised-dealer organizations are fighting Tesla for selling its electric cars in a way that circumvents the traditional franchised dealership system. On a positive side, dealers in 2014 are expected to see an increase of sales per store, a measurement of profitability.

Meanwhile, some state dealer associations say Tesla is short-circuiting the conventional dealer system by selling its vehicles directly to customers.

Tesla has opened small showrooms here and there where shoppers can check out the single-product Model S, then order one online from the manufacturer.

Some consumers think that’s the way to go. They see dealers as needless middlemen, and praise Tesla founder Elon Musk for trying to revolutionize how cars are sold.

Dealer associations and Tesla battled legally and legislatively over the EV maker’s desire to sell cars directly to consumers. Dealers say Tesla was circumventing dealer-franchise laws that exist in every state.

“What puzzles me is that he has never tried the franchise system, yet he insists it won’t work for him,” Bill Wolters, president of the Texas Automobile Dealers Assn., says of Musk.

Musk told the NADA he will embrace the dealer-franchise model that’s prevalent in the U.S. once sales of his cars reach critical mass, Westcott says. “(Musk) is an interesting individual, and the car is wonderful. The only thing we differ on is the distribution system.”

Westcott says the dealer-franchise system creates competition among dealers, resulting in better prices for customers. He notes automakers such as Ford tried to sell vehicles directly to the public in the past and failed.

Franchised dealers enjoyed high sales and healthy profits throughout 2013. One reason for the brisk delivery rates was the increased availability of relatively low interest loans and a comeback of credit access for people with imperfect credit scores.

The return of subprime credit, which virtually disappeared during the height of the recession, was propping up car sales in the U.S., Westcott says. “Subprime is back to where it should be. It had to be, to sell cars. We need that part of the segment.”

Average vehicle sales per U.S. dealership in 2013 were on track to set a record for the second year, said John Frith, vice president-retail solutions for consultancy Urban Science.

At the pace of auto sales for the year, the average sales per dealer, or throughput, would surpass 840 units.

A record was set in 2012 when sales per store averaged 812 vehicles, compared with 719 in 2011. Before that the all-time high was 784 eight years ago.

In the previous throughput high-water mark year of 2005, more than 21,600 U.S. dealers sold about 17 million vehicles.

The U.S. began 2013 with 17,851 dealerships. The number of stores dramatically fell by about 4,400 in 2008 and 2009. That was mostly because of General Motors and Chrysler consolidating their retail networks as part of bankruptcy reorganization.

“We have fewer vehicle sales, but also fewer dealers,” Frith said. “They are selling vehicles more efficiently,” by leveraging Internet leads, using better sales processes and completing customer transactions more quickly.

The low point for throughput was 513 units in 1991 when 24,200 dealers sold about 12.2 million vehicles.