Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

Once again, we are going to elect a president without a serious discussion on jobs and trade.

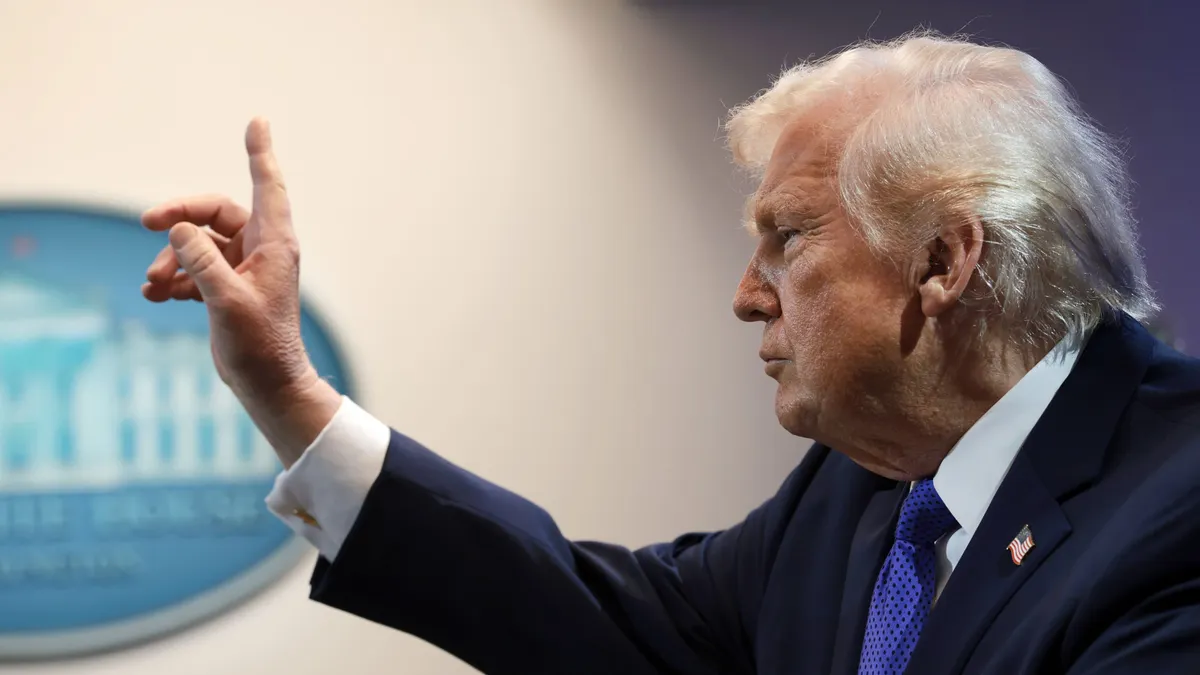

Donald Trump, who is running on a platform to “Make America Great Again,” has offered few specifics about how he would create new jobs or bring back old. Trump of course blames bad trade deals for plant closures in states such as Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania and has declared the NAFTA trade deal with Mexico and Canada as Public Enemy No.1.

Hillary Clinton, who didn’t vote for NAFTA or its latest incarnation, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, yet supported them in an earlier life, hasn’t told us what she’d put in their place now that she seems to have reversed her position on the TPP trade pact, one of President Obama’s initiatives. Basically, the main new take from her campaign is that she’ll end tax breaks for companies outsourcing jobs overseas.

Lest we forget, Clinton’s husband, former President Bill Clinton, signed NAFTA into law in 1993 with the support of 159 Republicans and 136 Democrats in Congress, including two former speakers of the House – Newt Gingrich, a Republican, and Nancy Pelosi, a Democrat – and Mitch McConnell, current Senate majority leader.

Rightly or wrongly, NAFTA was a bipartisan initiative.

Without getting mired in a lengthy discourse about the merits and demerits of free trade, it is worth mentioning, since neither candidate has offered a coherent plan, that in the early 1980s a trade agreement between the U.S. and Japan involving the auto industry produced tangible results, both in terms of creating jobs and bringing capital and technology into the country.

Falling under the rubric of “managed trade,” the (not so) voluntary export restraints negotiated by the Reagan Admin. did exactly what Trump promises to do (create jobs) and what Clinton promises not to do (let more jobs leave the U.S.).

Japanese automakers agreed to limit car exports to an average 1.8 million units over a 5-year period, ranging from 1.7 million in 1981 to 2.3 million in 1985. The total did not include pickup trucks which one year earlier, in April 1980, were slapped with a 25% tariff.

Triggering the decision was an economic slowdown caused by OPEC’s 1979 move to raise oil prices. The result: The American auto industry went into a tailspin. Ford, Chrysler and General Motors all bled red ink and the Japanese filled the breach with smaller, fuel-efficient cars.

The surplus in bilateral trade ballooned to $50 billion in Japan’s favor, three-quarters of which were cars and light trucks. Vehicle exports to the U.S. more than doubled over a 5-year period from 919,950 units in 1970 to 2.4 million in 1980 including 1.8 million cars.

The Japanese again chose discretion over valor, and one by one announced plans to build vehicles in the U.S.

First was Honda, which opened a plant in Ohio in 1982, followed by Nissan in Tennessee in 1983, Toyota in California in 1984 and Mazda in Michigan in 1987.

A second wave was influenced by the “Group of Five” industrialized nations’ move to depreciate the dollar against the yen and other leading currencies in September 1985, cutting sharply into export profit margins as the dollar lost nearly half of its value over the next three years and 60% over the next decade.

If government-imposed restraints on exports didn’t solve the problem, then exchange rates surely would. At least that’s what many people thought.

Resulting from the G5 and Plaza Accord, Toyota and Mitsubishi moved to set up shop in Kentucky and Illinois in 1988, Fuji Heavy Industries (Subaru) and Isuzu in Indiana and Honda again in Ohio in 1989, along with hundreds of suppliers.

Bridgestone, which had built its own plant in Tennessee and committed to a second facility, anted up $2.6 billion to buy Firestone’s global operations including seven tire plants in North America, three of which it subsequently closed including Decatur, IL, which was widely blamed for the Ford Explorer rollover problems and recall.

Although numbers vary, the tire maker reportedly saved 30,000 American jobs that would have been lost had Firestone gone bankrupt.

Through all of this, Japanese automakers continued to export vehicles to the U.S.: 2.2 million units in 1990 and 1.2 million in 1995, rebounding to 1.7 million in both 2000 and 2005 and 1.6 million last year.

Marcie Kaptur, representing Ohio’s 9th Congressional District, which stretches from Cleveland to Toledo, complained to me in a 1992 interview that “There had been an understanding that as the transplants built production facilities in the United States, the number of vehicles coming in from Japan would whittle down to almost nothing and exports would be replaced by production in the U.S.”

It didn’t work that way.

On the other hand, fast-forwarding to today, Japanese automakers have invested $45 billion in their U.S. operations. According to the Japan Automobile Manufacturers Assn., they operate 26 manufacturing plants, including 12 vehicle-assembly plants, and 27 R&D facilities in 17 states. They employ nearly 90,000 workers, including 61,000 in manufacturing and 5,000 in research, engineering and design.

In 2015, Japanese automakers built 3.9 million cars and trucks and 4.6 million engines. U.S. production accounted for 75% of sales.

They purchased $67.9 billion in U.S.-made parts, many produced by Japanese suppliers such as Denso, Aisin and Calsonic Kansei, which have extensive operations inside the U.S. Their investment is not counted in the JAMA total, although the industry association estimates Japanese suppliers – either directly or indirectly through partners – have created or saved an estimated 1 million U.S. jobs.

There are two postscripts to the story.

Because of the Japanese success, South Korean and German automakers followed suit. BMW set up U.S. assembly in 1994, followed by Mercedes in 1997, Hyundai in 2005, Kia in 2009 and Volkswagen in 2011. There were two casualties along the way, Mazda and Mitsubishi, neither of which builds vehicles in the U.S. any longer. Mazda subsequently opened a greenfield plant in Mexico, while Mitsubishi, now owned 34% by Nissan, may or may not relaunch local production with its new partner. It’s too soon to say.

Also, the quality gap between Japanese and American OEMs has narrowed to a point where they’re negligible. According to the J.D. Power initial quality study, Toyota, tops among Japanese brands in 2016, came in at 93 problems per 100 vehicles. Chevrolet, Buick and Lexus followed at 96. It wasn’t that way 35 years ago.

So, back to the election. Will resurrecting an old Reagan Admin. policy bring jobs back to the U.S. in other industrial sectors? Perhaps not. But it’s worth taking a look at. And although export restraints on Japanese cars did not undo the damage done to traditional manufacturing states such as Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania, they did create jobs elsewhere as the industry expanded into Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi.