Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

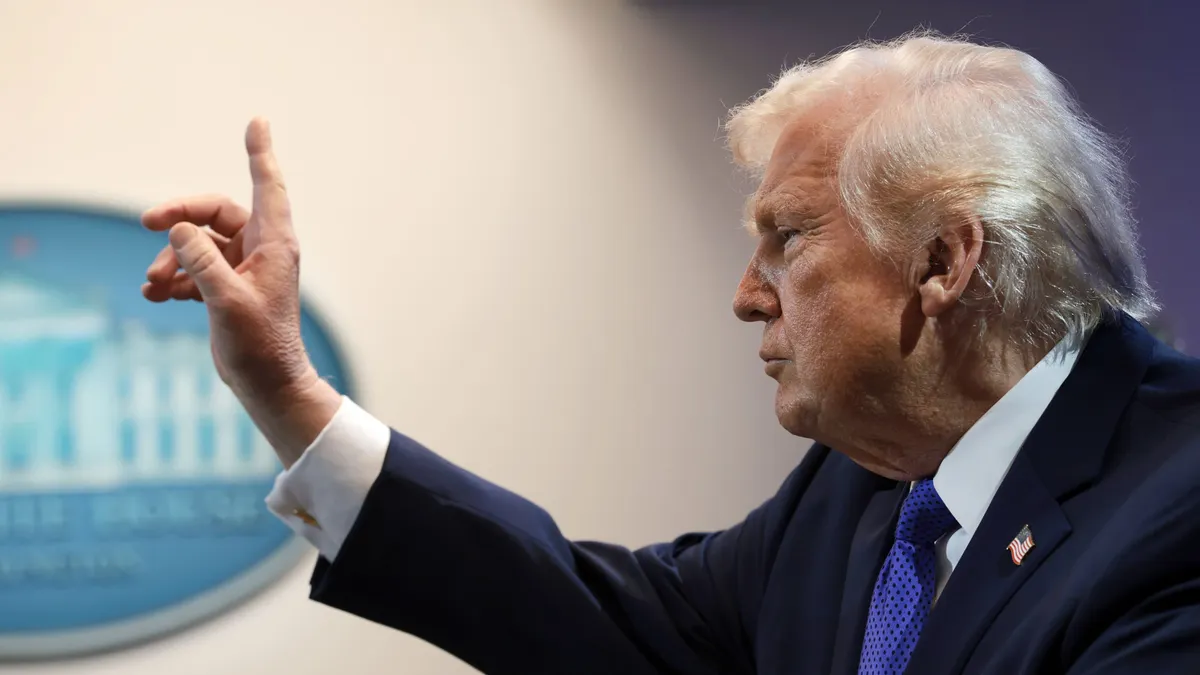

TRAVERSE CITY, MI – Midterm grades are in for the Trump Admin.’s automotive trade policy, and they’re not good.

And if we are to believe the warnings of industry experts at the Center for Automotive Research’s Management Briefing Seminars earlier this month, matters could get worse.

In the first big report card following the conference here, the U.S. International Trade Admin. revealed Aug.11 that the U.S. trade deficit in automobiles and parts had grown by more than a record $10 billion, 10%, between January and June, while in all key markets, including China, the deficit worsened or remained unchanged.

In China, the focal point of the administration’s most far-reaching tariff war, both imports and exports fell by $1.4 billion. Thus the big losers would appear to be automakers which source components from China and now must pay more for them in addition to BMW and Mercedes-Benz, which export upscale cars from their plants in South Carolina and Alabama.

In 2018, BMW exported 48,537 U.S.-built vehicles to China, one-third of U.S. exports to the market. Mercedes-Benz declines to provide its U.S. export numbers.

Meanwhile, Mexico, under the threat of tariffs for much of the year, registered record imports, up 13%, to $66.4 billion. Mexico, for the moment out of the line of fire as it awaits U.S. and Canadian approval of the new U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, now accounts for 35% of global imports of automobiles and parts into the U.S., which ballooned to $188.0 billion, another historic high.

Even the European Union, accused by the U.S. Commerce Dept. along with Japan of being a national security threat, registered 3% growth in imports while the EU’s trade surplus spiked 21%, from $8.6 billion to $10.4 billion.

The trade numbers, while potentially problematic, have been elevated in importance by the administration’s “just-give-me-a-reason” tariff policy, to quote Christine McDaniel, a senior research fellow and economist at George Mason University, who spoke at CAR’s three-day conference.

Kristin Dziczek (below, left), the center’s vice president of industry, labor and economics, questioned whether the administration is “out of ammunition” in its multifront trade war. “Does the administration have anything other than tariffs in its tool chest?” she asked.

Dziczek further warned that if the administration were to impose still-pending Section 232 “national security” tariffs on Japanese and European automobiles and auto parts, coupled with earlier 232 tariffs on imported steel and aluminum, the result would be a $2,500 higher sticker price on vehicles produced and sold in the U.S.

Since assuming office, the administration has pulled out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, threatened to withdraw from NAFTA, imposed 25% tariffs on imported aluminum and steel (Canada, Mexico and South Korea have been granted exceptions), raised tariffs from 10% to 25% on Chinese automobiles and parts, and threatened Section 232 tariffs against the Japanese and European auto industries.

The result has been uncertainty in the marketplace.

“If we impose tariffs on imported autos and parts (from Europe and Japan), it will devastate this industry and our economy,” warned Ann Wilson, senior vice president for government affairs at the Washington-based Motor and Equipment Manufacturers Assn.

“We are not a national security risk, period,” she declared, adding: “We really have to focus on what can give us some level of certainty.”

Jeff Schuster, president-Americas Operations at LMC Automotive, said: “The level of risk and uncertainty is real and not going away. And the high level of uncertainty affects decisions to invest.”

Market analyses from LMC, the Center for Automotive Research and BofA Securities paint a worrisome picture about where the market may be headed.

CAR predicts U.S. light-vehicle demand will fall to 16.2 million units in 2021, from 17.2 million in 2017 and 2018. More problematic, U.S. production is projected to fall this year to 10.4 million from 11.3 million in 2018, as automakers expand capacity in Mexico.

John Murphy, managing director and lead U.S. auto analyst at BofA Securities, sees even sharper declines with demand falling to 13.6 million units in 2022.

Globally, BofA (formerly Bank of America Merrill Lynch) expects plant utilization to fall to 63% in 2019 with idle plant capacity growing to 48 million units, then 55 million in 2020.

BofA predicts global light-vehicle demand, having peaked at 95.3 million units in 2017, will fall to 92.3 million this year and won’t recover fully until 2023 and beyond. The main reason, in addition to a weakening of the U.S. market, is flat or no growth in China, Europe and Japan.

Against this backdrop are growing fears of a recession. Bernard Swiecki, CAR’s assistant director of industry, labor and the economics group, warned: “We don’t actually need a recession formally. What we need is for people to start spending as if there’s a recession. And then you have the same negative impact.”