Smarter Approach to EV Battery Requirements Could Lower Costs

Experience with EVs may be giving automakers and battery suppliers the confidence to cut back on some of the costly over-engineering.

DETROIT – Battery suppliers continually are looking at ways to increase electric-vehicle range and lower costs by improving battery chemistry and manufacturing efficiency. Now they finally may be getting some help from automakers, as well.

Denise Gray, president and CEO of LG Chem Power, tells WardsAuto vehicle manufacturers are beginning to fine-tune their specifications in ways that could lead to more economical batteries, potentially making EVs available to a wider audience.

As automakers get more and more experience with EVs, they are starting to reconsider how battery power is allocated and how durable the energy-storage systems need to be, Gray says, suggesting not all batteries need be capable of delivering sports-car-like acceleration with 200-plus mile (322-km) range and greater than 100,000-mile (161,000 km) life expectancy.

“It’s the balance of the equation,” Gray says. “(Automakers) are looking at changing the variables. (They) are now open to what it is going to take to get to that next price point, and it’s not just, ‘Give me better materials or increase the manufacturing efficiency.’”

Until now the tendency has been to over-engineer batteries to avoid warranty issues and ensure customer acceptance for the emerging technology.

“(Electric vehicles) have been in the market six, seven, eight years now,” Gray says on the sidelines of the SAE’s World Congress Experience convention and exhibition here. “Now you’re determining, is my assumption on life accurate, is my acceleration factor on life (expectancy) accurate when I do my testing?

“You’re getting that feedback now to determine, did we overdesign it, did we over-specify it? That’s the beauty of having that time of experience and maturation that now goes back into your design.

“(Currently), we make one design that fits everybody, (but) can you tune it to (the needs of) a particular driver? If he is an aggressive driver, maybe you can adapt the life a little bit differently than for those who aren’t. There’s still a lot to be determined on how you balance cost with requirements.”

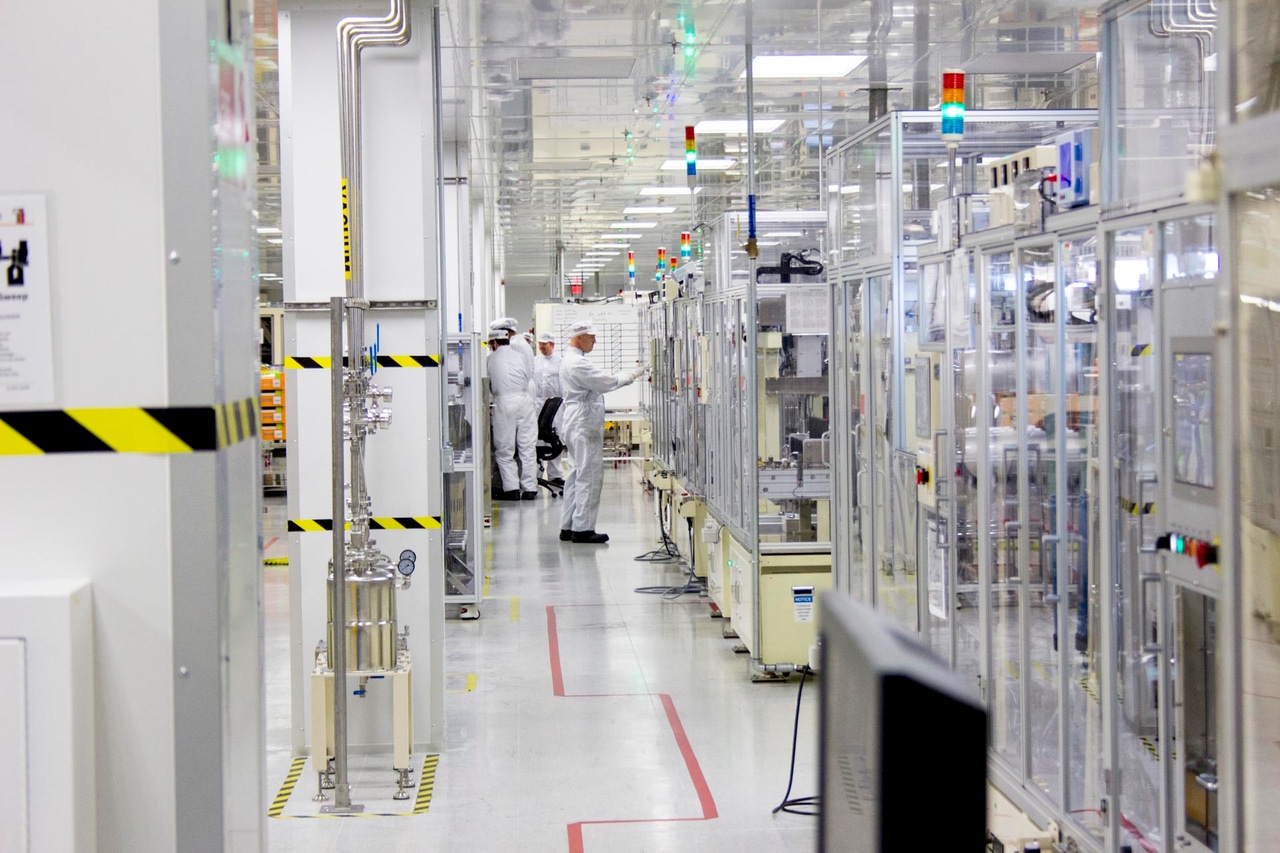

Gray: Industry smarter about right-sizing battery capacity investments.

Gray stops short of committing to any cost-reduction bogeys, saying everyone is working hard to achieve the $100/kWh target set by the U.S. Advanced Battery Consortium. Currently, costs run as low as $150/kWh.

“Those are aggressive for sure,” she says of the USABC target. “I think the decreases (in costs) over the last 10 years have been remarkable. And I think that has been enabled by the automotive OEMs and the battery-cell suppliers really working together.

“The next big step is before us, but it’s going to take a lot of work and a little bit of luck to get there.”

Gray says three factors have improved battery range and cost to date: better chemistry, more-efficient manufacturing and expanding volume.

“All three of those have allowed for the cost (reductions) to be achieved,” she says. “And I think it’s happened, quite frankly, because the industry has said, ‛We’re going to go down this path to electrification.’

“If we didn’t have that push to do it…it might not have happened as fast.”

Faster charging also is on the industry’s wish list, but Gray says matching the few minutes it takes to refill a vehicle with gasoline likely is out of reach. The USABC’s target of a half hour or less, down from about two hours today, is seen as a more reasonable fast-charging goal.

“Charge time is one (thing) that can and should be improved,” she says, adding most people will charge overnight for routine commutes and only need fast charging for longer journeys. “(Then you might want) 80% full in 15 minutes or 30 minutes. We’re working very hard on that.”

Quick-change battery-swap schemes, once promoted as the long-range driving answer for EVs by automakers such as Tesla and suppliers such as Israel-based Better Place, are unlikely to come to fruition, she says.

“That’s a tough one,” she says. “For commercial vehicles maybe, but for passenger vehicles (the opportunities) are limited.”

In order to make a business case, such quick-change schemes ultimately would require standardized batteries so a variety of models from a number of vehicle makers could be serviced. But Gray doesn’t foresee EV batteries taking a uniform shape any time soon – nor does she think that would be a good idea.

“We are too early to standardize, because if you standardize around something that’s too costly, you’ve lost the battle,” she says. “I’ve made sure we’ve built our battery plants around flexibility, because in three or four years we’ll be moving on to something else.

“I don’t want to talk about standardization until (the battery) becomes a commodity, and right now there’s not commodity pricing.”

LG Chem has four plants around the world, one each in the U.S., South Korea, China and Poland, and it currently is in the process of expanding its U.S. operation in Holland, MI, that produces cells for the Chevrolet Volt and Bolt and cells and packs for the Chrysler Pacifica hybrid.

“We’re at capacity at our Holland facility,” Gray says. “We’re actually breaking ground to add more capacity there. We’ve got a couple more projects to do battery cells and packs – all U.S.-market opportunities.”

Despite more and more lithium-ion battery plants in the works worldwide, the LG Chem executive is not concerned supply will outstrip demand. That was the case early on as manufacturers took advantage of government incentives to build Li-ion battery production capacity well beyond initial EV and hybrid sales.

“I think people are smarter today with their investment than they were a decade ago,” she says. “We’re working closely with OEMs to make sure we don’t put in more than they will use. You can never guarantee the volume…but we’re being very cautious about installing more capacity.”

[email protected] @DavidZoia

About the Author

You May Also Like