Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

Dave Cantin started as an 18-year-old dealership salesman right out of high school in New Jersey. By the age of 21 he was a senior manager at the store.

He went on to invest in the Brad Bensen Automotive Group, becoming dealer principal of its Hyundai dealership in New Jersey, one of the brand’s biggest outlets in the U.S.

After selling his dealership interest, Cantin, 39, established the Dave Cantin Group, a company that offers a range of services relating to the buying and selling of dealerships.

Wards talked to him about that, what dealerships need most to run successfully, the changing landscape of auto retailing, his unusual childhood and more.

Wards: What’s the nature of your business?

Cantin: We take a deal from A to Z. We represent the buyer and seller as a dual agent. It allows us to communicate with both sides in a timely fashion. We talk with CFOs, CEOs, attorneys and accountants. If you are communicating only through attorneys, it can drastically slow down getting to the finish line. And it costs more.

Wards: Is yours a unique business model?

Cantin: Very. One of the things we offer is assistance with the manufacturer franchise-application process. My COO has been in the auto sector for 35 years, worked for General Motors for two decades. He has an incredible ability to work with the factories.

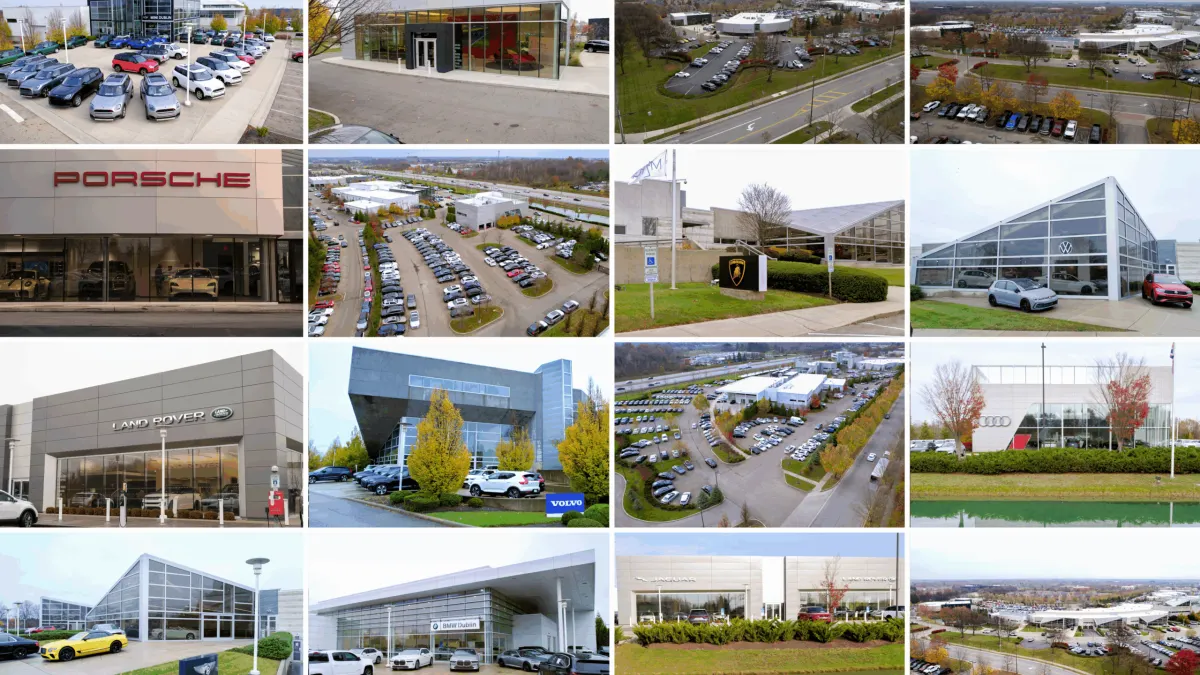

When we did the Prime Motor Group, which is 30-plus dealerships in New England, we got every single store packaged and approved within 180 days. That’s the second-largest acquisition in U.S. history behind Warren Buffet’s Van Tyl deal.

Wards: Your work includes succession planning, right?

Cantin: Anyone can sell a car dealership; the market will tell you what it’s worth. We create the acquisition. The majority come from succession planning, something that is not done enough in the industry today. We learned that two-thirds of the auto retailing industry doesn’t have a succession plan. That means people aren’t protecting their legacies.

Wards: Why do you suppose that’s the case?

Cantin: Nobody thinks about it. It can occur when you have a dealership that has been owned by the same family for 100 years or owned by someone who started it from scratch. We deal with this time and again.

Wards: Is it avoidance? One of those situations where you have a variety of relatives – siblings, cousins, grandchildren, whomever – involved in the family business, and the dealer principal says, “I’m not wading into the waters to try to figure out future ownership.”

Cantin: I’ll give you a perfect example. At 32 years old in 2011, I’m living the perfect American dream. A young daughter and son. Just got done building a house. Running an incredible business. Training to run the Boston marathon.

But then I began feeling sluggish. I go to the doctor because I was running out of energy. He does tests. He said, “Your white-cell blood count is 300,000, normal is 10,000.

Wards: I’m guessing leukemia?

Cantin: Yes. I’m checked into the hospital. I’ll never forget this image. A doctor with an entourage of physicians behind her walks into my hospital room. She says, “You just hit the lotto.” I said, “How?” She said, “You have CML – chronic myeloid leukemia. By you going to that doctor as soon as you did, you saved your life.”

I was supposed to be in the hospital for 60 days. I was exercising in the hospital, doing pushups with an IV in my arm. Day 16, I checked myself out. Ran the Boston Marathon. I was on chemotherapy every day for five years.

I never said, “Why me?” I think my attitude was a big factor in getting cured. I go back for tests every few weeks. So far, completely undetectable.

The reason I bring that story up is to show anything can happen to anyone. Dealers lead hectic, busy lives. Most don’t think, “What happens if I’m not here doing this, making these decisions?” Dealers need succession plans. It’s what we focus on the most. It’s about protecting your legacy. It destroys the value of the business if there’s not a succession plan.

Wards: Manufacturers are fussy these days regarding who takes over a dealership, so they don’t automatically approve any potential successor.

Cantin: Very fussy. Many sales and service agreements make you create a succession plan. It’s not just about a catastrophic event. It’s about what the next generation can do. They can either take it to the next level or sink the ship.

Wards: So it’s a one-two process in which you first do the succession plan and then the merger and acquisition?

Cantin: Succession planning is part of a merger and acquisition. The latter could be at a later date. Part of succession planning is finding out what the real value of a dealership is.

Wards: Surely, there are all sorts of reasons, but typically why does a dealer sell his or her business?

Cantin: The obvious reason is retirement. We’re seeing less of the next generation taking over. Twenty years ago, that was common. Today, it’s not. A lot of dealers will set up their general managers to take over. It varies.

In any acquisition, the operator is the most important component. Not the location or brand. You can have the best brand at the best location but without a good operator you can go out of business.

Wards: Who typically buys a dealership today?

Cantin: You have the six publics obviously. Half of them are looking to grow, half right now are looking at infrastructure and looking to tighten operations, maximizing efficiencies, customer-service satisfaction and synergies among stores.

The top 30 private dealership groups are starting to dominate the industry. They train their operators to work under established processes and they are careful at what they buy. They usually don’t buy one store at a time but a small group of three or four stores.

We created the second-largest automotive acquisition in U.S. history – GPD Capital purchasing Prime Motor Group – with 89% of the $1 billion acquisition money coming from private equity. A lot of private-equity businesses are buying into dealerships.

Wards: Some industry people feel private equity’s involvement in auto retailing can be dangerous with people who don’t know the industry coming in and looking to flip a short-term investment.

Cantin: You absolutely must know what you are doing. Dealing with private equity is great in many aspects, because it allows you the opportunity to grow with a partner.

When you are dealing with (financial) institutional money, they are not really a partner. They are lending you the money, but they aren’t there with you.

Wards: What does it do to the culture of a store if everyone realizes the place is owned by a private-equity company that may not have a long-term vision for the dealership and could flip the store at any time? Isn’t that disruptive?

Cantin: It’s a good point. Most private equity wants to be in and out of an acquisition within five to seven years. Some like to stay in north of 20 years. But a private-equity group cannot buy 100% of a dealership. The manufacturers wouldn’t approve that. You will see a private-equity group investing in an operator. That’s what they look for.

Wards: Are operators hard to find?

Cantin: They are the hardest thing to find in the industry. There are so many stores underperforming because they lack a good operator.

Top dealership groups act like farm clubs by raising their own operators. Good dealer principals aren’t afraid to teach people below them everything they know. That’s how you grow, not by hiring (outside) people to run your stores. You hear these stories all the time; how a person who started out as a detailer or a lowly worker at a dealership ultimately becoming a manager.

Wards: Where is the industry going with dealership acquisitions? (Dave Cantin, left)

Cantin: I’ve seen the most in the last three years than ever in my career.

Wards: Why’s that?

Cantin: It’s easier to get institutional and private-equity money.

Wards: How did you learn this business?

Cantin: I’ve always been involved in the finance world. Since I was 18. A lot of it is educating yourself. I learn every day. My upbringing was a lot different than most people’s.

Wards: How so?

Cantin: When I was nine, my father walked out and never turned back. My mother went into a state of depression, sleeping 22 hours a day. I raised myself from nine to 18. At nine, I learned how to self-motivate; how to get yourself out of bed, how to get yourself to school, how to guide yourself through school. You learn to overcome hardships.

As part of a school co-op program, I sold women’s shoes at Nordstrom’s as a high school junior and senior. That was educational. When I graduated, I talked my way into a job at a local dealership which at first wasn’t sold on the idea of a teenage salesperson. But I persisted. I believe in getting better every day.