Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

After years of historically robust car sales, the new economy demands more attention to the details of daily business. Ignoring or not understanding data undermines profitability.

What is actually going on in new, used, finance and insurance, parts and service and in the body shop? Do your managers know how to use expense management and balance sheet controls to fully take advantage of every profit or expense reduction opportunity?

Can they manage the balance sheet through exceptions to identify frozen cash, and then act to get that cash flowing again?

“Most managers today continue to manage volume and expense structures based on their past experience,” says Rick Kotzen, a CPA and partner, Retail Dealers Practice for Crowe Horwath LLP.

To improve on that, it's essential to gain access to data. But it can be hard getting it from the dealer-management system and into a format that non-financial managers can understand.

New performance software makes it easier to extract financial data. Having gross, expense metrics and balance-sheet exceptions at hand helps managers improve performance, manage risk and measure progress.

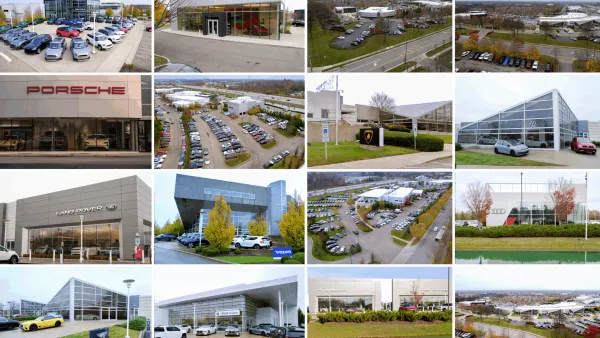

The need for managers to work the “real” numbers holds true for dealerships of any size, including multi-point and mega dealership groups.

“But when you say to general managers that they have to change their cost structures to get to a better bottom line, too many simply are unsure or lack the experience on how to execute,” Kotzen says.

“They need a new playbook that presents financial data so they understand what it means and then can use it to affect the necessary changes,” he says.

Financial measurement and improvement tools, such as Crowe Navigator, can give managers daily and prior-period profit and loss information, unit sales booked to accounting and F&I, vehicle sales, and gross profit numbers for various departments.

Take a dealership's pre-owned department where the manager appears to be doing a good job of keeping inventory levels right and vehicles are selling. Do the numbers back that up?

The analytics may show that the average cost of 100 cars in inventory is $17,500, yet the average selling price for units sold is $14,000. The conclusion: The mix of inventory is not correct because it's heavy on higher-cost units but sales tilt toward more lower-priced units.

Another example: The new- and used-vehicle departments, noticing grosses declining, pushes more F&I products. But to do, it must increase commissions.

A drill-down into the daily data (and comparing it to daily data from last week, month or year) reveals that commissions are actually growing at a faster rate than the gain in increased F&I gross profit.

Executive management can use that data to restructure F&I compensation to better match the selling environment and drive net departmental profitability.

“One has to be able to look into the various financial components of the business to identify what actions or policies are making performance better or worse,” says Mark Blosser, also a partner and CPA with Crowe's Retail Dealers Group.

“How do you increase or eliminate the issues that are bringing you backwards? What can you learn from the balance sheet about what is tying up your cash? Are contracts in transit over 10 days or factory warranty receivables over 30?”

Managers historically have not done a good job of managing cash receivables and inventories, he says. “It's a piece of management that is highly overlooked in the auto industry.”

Fred Kirschbaum, CFO for the Checkered Flag Motor Car Co., Virginia Beach, VA. He manages the financial health of the company's six stores using a performance tool.

“It reveals the day-to-day small things that if ignored can add up to big risks to gross increases or expense control,” he says.

For instance, he tracks contracts in transit across all stores and drills down into each to check its status.

“We're waiting for this cash to come in, so I want to know why we're not getting paid,” Kirschbaum says.

Walt Sullivan, a consultant to Summit Motor Management Inc., and formerly its director of internal control, likes providing department heads with daily numbers that compared with expenses, sales and grosses of the top 10% of similar-sized stores.

It helps managers benchmark where they should be, he says. “And when managers know their boss is reviewing this data, too, it keeps them on their toes.”