Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

A study commissioned by the American Financial Services Assn. disputes a federal agency’s allegation of racial lending disparities.

The study involving more than 8.2 million auto financing contracts says data fails to support the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s disparity allegations of differences in the amount of dealer reserve charged to minorities and non-minorities.

The association’s research cites significant bias and high error rates in the proxy methodology the CFPB used in reaching its conclusions last year.

“AFSA’s results are much lower than what the CFPB alleges as problematic in the marketplace, because the association’s study factored in complexities of the automotive market that the CFPB did not consider,” AFSA President and CEO Chris Stinebert says.

He adds, “The interplay between factors such as geography, new vs. used, length of loan, down payment, trade-in vehicle, credit score and competitive factors, such as meeting or beating a competing offer, is evidence of a dynamic market.”

Central to the study was an examination of the Bayesian Improved Surname Geocoding (BISG) proxy methodology used by the CFPB to determine disparate impact to legally protected groups.

BISG estimates race and ethnicity based on an applicant’s name and census data. AFSA’s study calculated BISG probabilities against a test population of mortgage data, where race and ethnicity are known. Among the findings:

- When the proxy uses an 80% probability that a person belongs to an African American group, the proxy correctly identified their race less than 25% of the time.

- Applying BISG on a continuous method overestimates the disparities and the amount of alleged harm and provides no ability to identify which contracts are associated with the allegedly harmed consumers.

“Alleged pricing discrepancies between minorities and non-minorities for auto financing rates are simply not supported by data,” Stinebert says.

His group has reviewed study results with the CFPB and anticipates “continuing our work with the bureau to address the issues we raised and to ensure consumers have access to affordable credit,” he says.

Charles River Associates conducted the study and examined 30% of all new and 10% of all used retail installment contracts financed during 2012 and 2013.

An executive summary of the study is available here.

Defenders of dealer-assisted financing, which accounts for most auto loans, rebut the government discrimination charges, and question how such conclusions were reached.

“We want to make the case correctly, with accurate statistics,” Stinebert said earlier this year in announcing the trade group’s plan to commission the study.

The CFPB criticizes the so-called dealer-reserve system in which dealers increase loan rates by varying percentage points as payment for acting as middlemen between lenders and car buyers.

The long-standing practice gives dealers the discretion to set final consumer-loan interest rates. That’s caused rate discrimination against minorities, the CFPB says.

Its analysis led to a settlement case in which the federal government is making Ally Financial pay $80 million in restitution and $18 million in fines because some of the lender’s dealer clients allegedly charged higher loan rates to African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians and Pacific Islanders.

CFPB says the alleged discrimination appears unintentional.

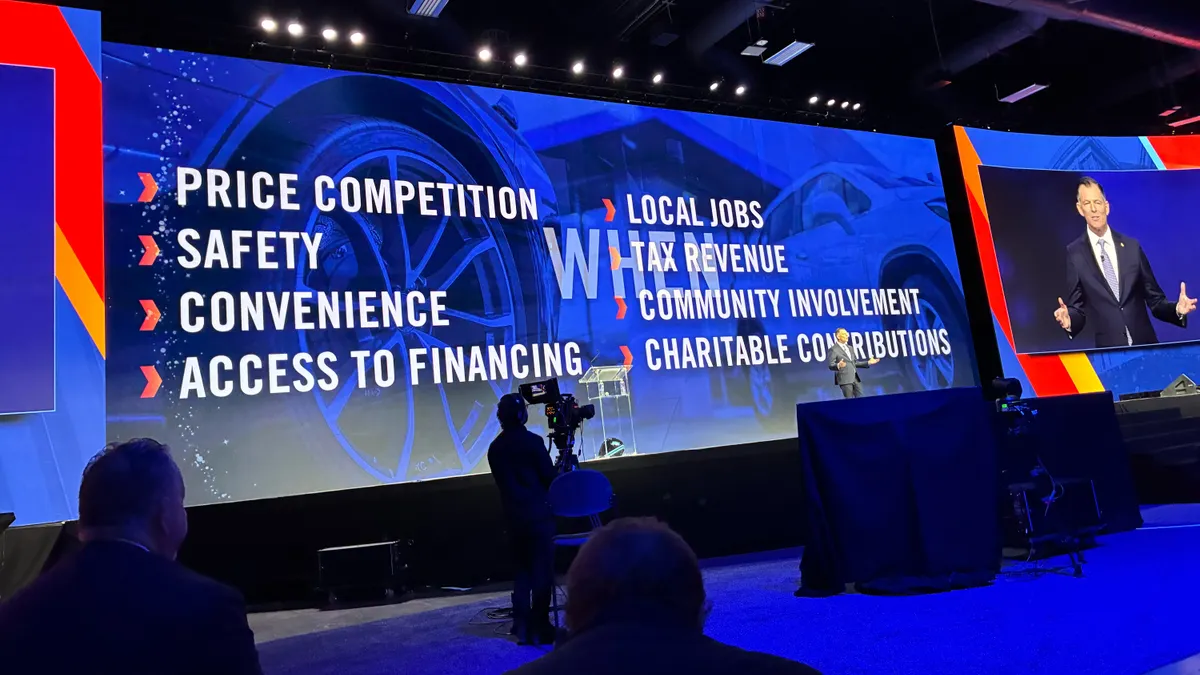

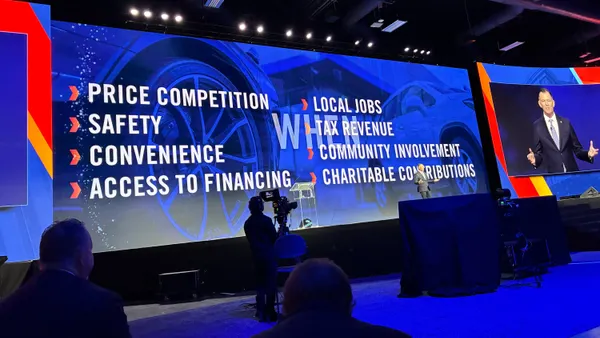

Credit scores were not a factor in gauging rate disparities, Patrice Ficklin, CFPB assistant director-office of fair lending and equality opportunity, told an AFSA conference held in conjunction with this year’s National Automobile Dealers Assn. convention.

The government analysis involved Ally retail-installment contracts from April, 2011 to March, 2012. Twenty percent of those contracts involved minority groups, Ficklin says.

In doing the analysis, the CFPB and Department of Justice did not know for sure which borrowers were minorities. Instead, the agencies “assigned race and national-origin probabilities,” Ficklin says, citing “geography-based and name-based probabilities” drawn from U.S. Census Bureau data.

The government says loan basis points were higher by 29 (0.29%) for African Americans, 22 (0.22%) for Asians and 20 (0.20%) for Hispanics.

Such disparity would end or abate if “dealer markups” were replaced by flat fees or something similar, Ficklin says, calling the government analysis statistically significant.

Ally issues this statement in response to the study:

“Ally appreciates that AFSA has taken a data-based approach in studying the industry, and the report further supports our previously stated concerns with the BISG proxy methodology and the portfolio level analysis that it drives.

“As demonstrated in the AFSA study, there are clear limitations in using the BISG proxy methodology to assess disparate impact in auto financing.

Ally believes that all consumers should be treated fairly when pursuing an auto financing contract, and the company does not condone or tolerate discrimination.”

The company adds: “The most prudent course is for finance providers, dealers and other participants to come together to determine an industry-wide solution that addresses the issue of disparate impact without triggering significant unintended consequences.”