Editor's note: This story is part of the WardsAuto digital archive, which may include content that was first published in print, or in different web layouts.

The automotive chip supply crisis started in 2020 after new-vehicle demand bounced back earlier than expected, and chipmakers did not immediately switch capacity back to automotive-grade tech. Two years later, automakers still are shutting down production due to a lack of chips.

Kristin Dziczek, automotive policy advisor for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, explains why automakers are still battling the chip shortage and why that struggle is expected to continue a bit longer.

First, automakers are using more chips per vehicle. Having a limited supply, automakers prioritized the most profitable vehicles, which tend to be the higher-end models. That exacerbated the supply problem, as these models require more chips due to the more sophisticated advanced driver-assistance system, cockpit and HMI features.

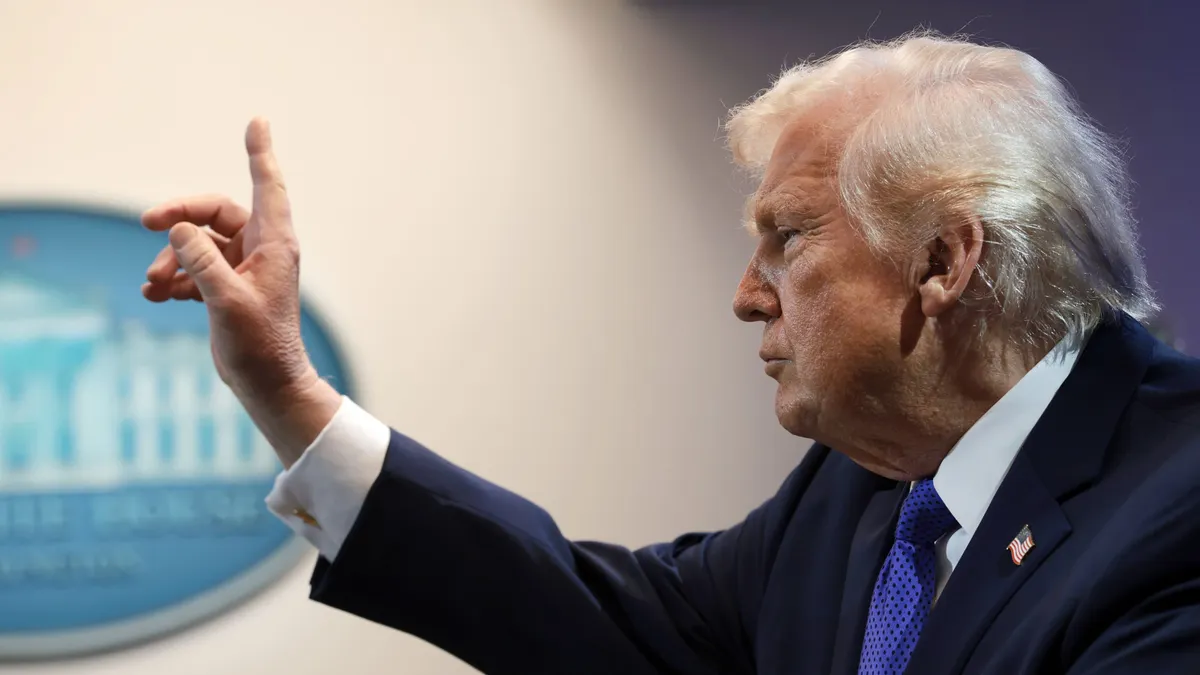

Dziczek (pictured, below left) points out, “Each car requires more chips, and if we had all the chip supply we had in 2019, we (still) could not make the same number of vehicles that this industry made in 2019.”

Second, there is a mismatch between chips and vehicle lifecycles. A vehicle platform has an average development cycle of three years, and production runs for seven to nine years. This is a period over which a semiconductor supplier will have launched several new chip generations.

“The chip industry wants to move fast and change, while the automotive industry wants to buy the same chip for 10 years. (However), they are not majority buyers of high-end chips and (hence) have low market power,” Dziczek says.

The lengthy and costly supplier qualification process and the need to maintain and repair vehicles for 10 to 12 years once they are out on the road are the reasons why the automotive industry moves slower.

Third is the high reliance on legacy technology. Despite the ongoing transition to powerful computers in cars, the average internal-combustion-engine vehicle relies almost entirely on mature chip technology, which provides limited revenue to semiconductor suppliers.

“It is difficult to make the (return on investment) for expanding mature chip capacity, because it is still costly, especially considering that (capacity) could be built or allocated for higher-end, higher-margin chips,” Dziczek tells Wards.

Although in the U.S., the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) Act provides $2 billion for mature technology growth, this is proving insufficient incentive for chipmakers due to the fourth reason for the ongoing crisis: the unreliability of the automobile industry.

“Does it make sense for chipmakers to put more money into mature technologies for automakers when the auto industry is so fickle? As soon as times got tough in 2020, they pulled back,” she says.

Another aggravating factor is the transition to software-defined vehicles that use high-end chips because, Dziczek says, “(Automakers) will depend on this mature technology until they do not.” Therefore, chip manufacturers are being cautious and demand long-term commitment before making significant investments, even when funding is available. For chipmakers, automakers’ transparency about their sales forecasts also is vital to manage the crisis.

According to Dziczek, co-investments will be the best alternative for mature chip supply going forward: “Automakers need this tech, but they know the chip suppliers’ margins on mature technology are low, so they will provide financial help in building or maintaining capacity.”

However, this will not work in the short term and, at least for now, vehicles will continue to ship with missing chips. So far, demand is so strong consumers are willing to take cars with missing features, but as demand and supplies start normalizing, consumer satisfaction with incomplete vehicles will drop.

“Automakers best organized and positioned to tackle this crisis will have a competitive edge,” Dziczek says. “(Also), the ability to have dealers retrofit the missing chips at a high quality will be a differentiator.”

Policymakers are doing their part to alleviate the crisis. Many years of regarding chips as a consumer rather than a military product led to a highly globalized supply chain. Although change cannot be forced overnight by saying all production steps must happen locally or in allied countries, the supply crunch will not change unless there are investments in new capacity, R&D, training and workforce, which are addressed in the U.S. CHIPS Act and are being copied by several other nations.

“(Moreover) the Oct. 7 action from the Biden Admin. to cut off access to advanced technology to China was a breaking point in an increasingly global industry that is starting to pull back and regionalize,” Dziczek adds.

“In the auto industry, things go wrong all the time, but they work around it. In 2011, after the tsunami, Japanese suppliers got down into their supply chains and understood where everything was coming from, got better information and more transparency and were able to weather the next storm better. (Presently) chip buyers are trying to reduce to a smaller range of chips to make bigger buys and have more market power. They are (also) qualifying multiple plants instead of one source. Some things were on autopilot, as (Tier 1) suppliers would take care of the chip supply, so it is about learning more about where things are really coming from.”